Searching for High Energy Neutrinos

with the AMANDA-II detector

by

Jodi Ann Cooley-Sekula

A dissertation submitted in partial ful?llment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

(Physics)

at the

University of Wisconsin { Madison

2003

?

c

Copyright by Jodi Ann Cooley-Sekula 2003

All Rights Reserved

Searching for High Energy Neutrinos

with the AMANDA-II detector

Jodi Ann Cooley-Sekula

Under the supervision of Professor Albrecht Karle

At the University of Wisconsin | Madison

The Antarctic Muon and Neutrino Detector Array (AMANDA) is designed

to detect high energy neutrinos from extragalactic sources. It uses the south polar

ice cap as both a target and medium for detecting Cherenkov radiation from the

charged particles left after a neutrino collides with a nucleus.

Many models predict a ?ux of neutrinos from di?use extragalactic sources

(such as active galactic nuclei). In this work, a search is performed in data taken

during the austral winter of 2000 by the AMANDA detector. The search ?nds

4 events on a predicted background of 3.26 events. Therefore, for an assumed

E

? 2

spectrum a 90% classical con?dence belt upper limit on the ?ux is set at

4:8 ? 10

? 7

cm

? 2

s

? 1

sr

? 1

GeV for neutrinos in the energy range 12-2000 TeV. This

is currently the most stringent limit placed on this ?ux by any experiment.

Albrecht Karle (Adviser)

ii

To Mom and Dad who inspired me to dream.

iii

Acknowledgments

This work would not be possible without years of support and help from many

people whom I am proud to acknowledge. First, I'd like to thank my adviser

Albrecht Karle, who has o?ered me guidance, supported me through my years at

the University of Wisconsin and believed in me.

I would also like to thank the members of the AMANDA collaboration who

have built and maintained the experiment.

Closer to home, I would like to thank the \penguins" group who not only

o?ered their support and useful suggestions, but became good friends. I would

especially like to thank Gary Hill for his in?nite motivation and patience, never

giving up on me, and always o?ering his help and support. I would also like to

thank Paolo Desiati for all expertise and encouragement. Of course, I can not for-

get to acknowledge Bob Morse for keeping the whole thing running, Francis Halzen

for his motivation and eternal excitement, and Darryn Schneider for keeping the

computers running.

With all my heart I would like to thank my parents, Richard and Ann

\Tootie" Cooley and my siblings, Jackie, Jerry, and Jolene Cooley. Their love,

support, and encouragement has kept me moving toward my dreams ever since I

iv

was a child.

Finally, I would like to thank my husband, Steve Sekula who puts up with

it all and still has time to inspire me.

v

Contents

Acknowledgments

iii

1 Introduction

1

2 High Energy Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics

3

2.1 CosmicRays. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

2.1.1 FermiAcceleration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2.2 Neutrinos as a Source of Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

2.3 Expected Sources of Astronomical High Energy

Neutrinos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

2.3.1 TheAtmosphere . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

2.3.2 TheGalacticDisk. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

2.3.3 Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

2.3.4 Gamma Ray Bursts (GRB) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

2.3.5 ExoticPhenomena . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

2.4 Di?useSource . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

2.5 NeutrinoOscillations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

vi

3 Detection of Neutrinos

22

3.1 Neutrino-Nucleon Interactions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

3.2 LeptonSignatures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

3.3 MuonEnergyLoss . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

3.3.1 Cherenkov Radiation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

3.3.2 Stochastic Energy Deposition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

4 The AMANDA Detector

32

4.1 History. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

4.2 TheDetector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

4.3 DataAcquisition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

4.4 IceProperties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

5 Event Reconstruction and Analysis Tools

42

5.1 Direct Walk Reconstruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

5.2 Maximum Likelihood Reconstruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

5.2.1 TimeLikelihood. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

5.2.2 Bayesian Likelihood. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

5.3 QualityParameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

5.3.1 LikelihoodRatio . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

5.3.2 Smoothness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

5.3.3 Number of Direct Hits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

5.3.4 TrackLength . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

vii

5.3.5 ZenithAngle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

5.3.6 CenterofGravity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

5.4 The Model Rejection Potential . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

6 Data and Monte Carlo Simulations

52

6.1 Live-Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

6.2 OMSelection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

6.3 HitCleaning. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

6.4 Filtering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

6.4.1 Level1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

6.4.2 Level2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

6.5 BackgroundReduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

6.5.1 Level 3 - Electronic Cross-Talk and Muons from Cosmic Rays 56

6.5.2 Level 4 - Coincident Muons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

6.6 Simulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

6.6.1 MuonGeneration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

6.6.2 Photon Propagation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

6.6.3 Muon Propagation in Ice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

6.6.4 DetectorResponse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

7 Atmospheric Neutrinos

65

7.1 Level5-EventQuality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

7.2 Normalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

viii

7.3 Other Atmospheric Neutrino Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

8 Searching for a Di?use Flux of High Energy Neutrinos

88

8.1 BackgroundRejection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

8.1.1 CosmicRayMuons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

8.1.2 CoincidentMuons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

8.1.3 Background Atmospheric Neutrinos . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

8.2 Sensitivity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

8.3 E?ectiveArea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

8.4 Systematic Uncertainties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

8.5 Results. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

8.6 DiscussionofResults . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

8.7 OtherModels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

9 Conclusions

109

A Reconstruction Chain

119

B Quality Levels

120

C Atmospheric Neutrino Event Candidates

121

D High Energy Neutrino Candidates

131

ix

List of Tables

7.1 Passing rates of data and Monte Carlo simulations for various qual-

ity levels. The neutrino Monte Carlo has been normalized as de-

scribedin7.2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

8.1 Sensitivities and best number of optical modules ?red cut for vari-

ous detector live-times. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

8.2 Results for the three di?erent data samples. . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

8.3 Sensitivities for other models of high energy neutrinos. The op-

timal nchannel cut, predicted number of background events, and

predicted number of signal events are shown. The average upper

limit (??(n

b

)) and average model rejection factor are shown with

and without the inclusion of systematic uncertainties. . . . . . . 108

8.4 Experimental results for other models of high energy neutrinos.

The number observed, the predicted number of background events,

and the predicted number of signal events are shown. The ex-

perimental limits (event limit ?

o

? ?(n

o

;n

b

)) are given with and

without the inclusion of systematic uncertainties. . . . . . . . . . 108

x

A.1 Outline of reconstruction chain. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

B.1 List of cuts de?ning each quality level. The two dimensional cuts

in the two rows are de?ned by their slope and intercept. . . . . . 120

C.1 List of atmospheric neutrino events. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

D.1 List of high energy neutrino events for the blind sample. . . . . . 131

D.2 List of high energy neutrino events for the unblind sample. . . . . 131

D.3 List of high energy neutrino events for the combined sample. . . . 132

xi

List of Figures

2.1 The cosmic ray spectrum adapted from [12]. . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

2.2 First order Fermi acceleration by a plane shock front. Adapted

from[15]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.3 Second order Fermi acceleration by moving, partially ionized gas

cloud. Adaptedfrom[15]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.4 Neutrinos can travel from greater distances than photons because

they are not absorbed by ambient matter or photon ?elds. Fur-

thermore, neutrinos are not de?ected by magnetic ?elds and always

point directly back to their source, unlike cosmic rays [16]. . . . . 10

2.5 The atmospheric neutrino spectrum has a symmetric peak about

thehorizon. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2.6 Possible production mechanism for AGN. Electrons and possibly

protons, which are accelerated in sheets or blobs along the jet,

interact with photons that are radiated by the accretion disk or

produced in the magnetic ?eld of the jet. Taken from [17]. . . . . 16

xii

2.7 Expected ?uxes of ? + ?? intensities for emission from various di?use

sources taken from [21]. Fluxes 1-2 are predicted using the core

model of emission from AGNs [22, 23], while ?uxes 3-6 use the

AGN jet (blazar) model [24, 25, 26, 27]. Flux 7 is a prediction of

neutrinos from GRBs [28], while ?ux 8 is a neutrino prediction from

topological defects [18, 19]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

3.1 Charged-current neutrino cross sections as a function of energy [33].

The solid line is based on the CTEQ3 parton distributions. The

dashed and dotted lines are from older measurements. . . . . . . 24

3.2 Di?erential cross section for neutrino-nucleon scattering for neu-

trino energies between 10

4

GeV and 10

12

GeV from [33]. . . . . . 25

3.3 Energy dependence of the average in-elasticity of neutrino-nucleon

interactionsfrom[33]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

3.4 A muon event in the AMANDA detector. As the muon passes

through the detector, light is emitted at a constant rate. . . . . . 27

3.5 An electron event in the AMANDA detector. The electron quickly

dissipates its energy in an electromagnetic cascade, generating a

roughly spherical Cherenkov light distribution. . . . . . . . . . . 28

3.6 A tau event in the future IceCube detector. The two cascades of

light are produced by the initial neutrino-nucleon interaction and

subsequent decay of the tau particle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

xiii

4.1 Top view of the AMANDA-II detector. The radius of the detector

is approximately 100 meters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

4.2 Schematic of the geometry of AMANDA-II. AMANDA-A and AMANDA-

B10 are shown in expanded view in the center. An optical module

is blown up on the right. The Ei?el Tower is shown to illustrate

thescale. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

4.3 Absorption coe?cients as a function of depth at various wave-

lengths[38]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

4.4 Scattering coe?cients as a function of depth at various wavelengths

[38]. .................................. 40

4.5 Scattering coe?cient as a function of depth, indicating the presence

of dust layers. On the left side of the plot the depth of the OMs in

relation to the dust layers are shown [39]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

5.1 The prior function used is ?at over the up-going hemisphere and

dependent on zenith angle in the down-going hemisphere [36]. . . 46

6.1 The optical modules excluded from the 2000 analysis and their

status. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

6.2 A demonstration of cross talk. The data points that cluster to the

bottom-left of the solid curve are from cross talk. Taken from [48]. 58

6.3 Example of a coincident muon event in the AMANDA-II detector. 60

6.4 Events to the left of the line are primarily due to mis-reconstructed

cosmic ray muons and coincident muons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

xiv

7.1 The energy and zenith angle distributions of atmospheric neutrinos

simulatedfor197days. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

7.2 The zenith angle distribution plotted for events passing level 4 cri-

teria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

7.3 The zenith angle distribution plotted for levels 5.1 - 5.4 As quality

parameters are tightened, data and Monte Carlo simulations come

into agreement. The solid line represents data, the dashed line

represents atmospheric Monte Carlo simulations, and the dotted

line represents the E

? 2

Monte Carlo simulations. . . . . . . . . . 68

7.4 The zenith angle distribution plotted for levels 5.5 - 5.8 As quality

parameters are tightened, data and Monte Carlo simulations come

into agreement. The solid line represents data, the dashed line

represents atmospheric Monte Carlo simulations, and the dotted

line represents the E

? 2

Monte Carlo simulations. . . . . . . . . . 69

7.5 The likelihood of the events being up-going. Events to the right-

hand side of the plot are most likely to be from up-going neutrinos.

An excess of data events at lower values than the Monte Carlo simu-

lations indicates that these events are likely to have been produced

by down-going mis-reconstructed muons from cosmic rays rather

than up-going neutrinos. Events to the left of the vertical solid line

areremoved. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

xv

7.6 The distance covered by the muon passing through the detector.

Many mis-reconstructed tracks have lengths less than 155 meters.

Events to the left of the solid vertical line are removed. . . . . . 73

7.7 The distribution of the smoothness of the events in the detector.

High quality tracks have smoothness values near 0. Events between

the two solid vertical lines are kept. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

7.8 The number of hits in the detector with time residuals between -15

and 75 ns. A track with high quality would have many \direct"

hits. Events to the left of the solid vertical line are removed. . . 75

7.9 This ?gure demonstrates the disagreement between data and Monte

Carlo simulations for events that have more than 50 optical modules

?red. ................................. 76

7.10 This ?gure shows the disagreement in the smoothness distribution

for events that had more than 50 optical modules ?red. . . . . . 77

7.11 The direct length versus the negative log likelihood ratio of the

the events being track-like to shower-like plotted for events with

at least 50 optical modules ?red and positive smoothness. Events

above and to the left of the solid line are removed. . . . . . . . . 78

7.12 An event removed by the 2D cut on the length of the event versus

the track-to-shower likelihood ratio applied to events with more

than 50 optical modules ?red which had a positive value of the

smoothnessparameter. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

xvi

7.13 The track-to-shower likelihood ratio versus the center of gravity

of the event. Events near the top and bottom of the detector,

where optical modules are more sparsely placed, are required to

demonstrate higher quality than events with center of gravities near

the middle of the detector. Events below and to the left of the

diagonal solid line and the events to the right of the vertical solid

lineareremoved. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

7.14 The ratio of number of events observed to the number predicted

by Monte Carlo simulations of atmospheric neutrinos. The line ?t

at high event qualities shows the normalization factor used in this

analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

7.15 Neutrino energy for the three ?ux predictions used in this analysis.

Below 31 TeV the Lipari and Honda ?uxes agree to within 2.3%

while the Bartol ?ux predicts 23.9 % more neutrinos than the Lipari

?ux. .................................. 85

7.16 The number of optical modules ?red for each event for energies less

than 31 TeV plotted for the three models tested, Lipari, Bartol and

Honda. The number of events for each model has been normalized

totheLiparimodel. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

7.17 The number of optical models ?red during each event plotted for

data and the three models tested. The models have been normal-

ized to the number of data events. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

xvii

8.1 As selection criteria are tightened, the number of coincident muon

events for a year diminishes. In the region where the number of op-

tical modules ?red in events is between 50 and 125, an exponential

function can be ?t to levels 3 and 4. Extrapolating this function to

level 5.1 still shows agreement. Extrapolating to level 5.5 shows an

expectation of less than a hundredth of an event each year in the

signalregion(nch>80). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

8.2 The muon energy at the center of the detector for atmospheric

neutrinos (background) and E

? 2

neutrinos (signal) before and after

thenchannelcut. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

8.3 The above plots demonstrate a relationship between the number of

OMs ?red during an event and the reconstructed muon energy at

the center of the detector. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

8.4 The number of optical modules ?red during events. The dashed

line represents the background atmospheric neutrino Monte Carlo

and the dotted line represents the signal Monte Carlo. . . . . . . 95

8.5 E?ective area for the cuts used in this analysis. . . . . . . . . . . 97

8.6 Number of channels ?red for the unblinded data sample. . . . . . 101

8.7 Number of channels ?red for the blinded data sample. . . . . . . 102

8.8 Number of channels ?red for the combined data sample. . . . . . 104

xviii

8.9 Comparison of predictions of Charm and the SDSS model of AGN

to the results of this analysis. Also plotted are the AMANDA-B10

results and the AMANDA-II results (this work) for an assumed ?at

E

? 2

spectrum. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

9.1 Comparison of IceCube sensitivity after 3 years of operation to the

limitsetwiththiswork. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Mankind has long looked with curiosity at the night sky. Stars and planets pro-

vided not only a source of myths, but also served as valuable navigational tools.

This is likely the reason astronomy is among the oldest of sciences.

Up until the turn of the twentieth century, the only means of observing

the sky was with photons at optical wavelengths. During the twentieth century

photon astronomy expanded to new wavelengths. Modern astronomy looks at the

sky in every band from radio waves to gamma rays. These new ways of seeing the

universe paved the way for discovery. New objects and undreamed phenomena,

such as pulsars, active galaxies, gamma ray bursts, and more were revealed.

A de?ning development for astronomy came in 1912 when Victor Hess dis-

covered cosmic rays. This led to the use of protons and other nuclei as messengers

from space. These new messengers brought with them a whole host of questions

such as concerning their origin and the mechanism that accelerates them. These

questions still puzzle scientists today.

In the past decades a new particle, the neutrino, has lent itself to probing

2

solutions to these questions. As messengers from space, neutrinos have advantages

over photons and cosmic rays since they are not absorbed or de?ected at high

energies. The distance a photon can travel through space falls quickly at PeV

energies as its mean free path length is limited to the Mpc scale [1] while cosmic

rays are de?ected by magnetic ?elds as they travel through space.

The idea of using oceans as sites for large neutrino detector date back to the

1960s [2, 3, 4]. Early attempts to use neutrinos as messengers from space started

with the DUMAND project [5] in 1975. At the time of this thesis, there were

three operational neutrino telescopes (ANTARES, AMANDA-II, and Baikal) and

two neutrino telescopes in the development and prototyping stage, IceCube and

NESTOR.

Much time and care has gone into understanding how to calibrate and an-

alyze the data from the AMANDA experiment. These analyses have been the

topic of many theses and papers. The ?rst result, a glimpse of the atmospheric

neutrino spectrum as seen by the AMANDA detector, was published in a letter to

Nature in 2000 [6]. Since that time, AMANDA has further established itself as a

landmark scienti?c experiment and has published results of analyses on neutrino

point sources [7], di?use ?ux muon and electron neutrinos [8, 9], WIMPs [10], and

supernova [11].

This work has helped to pave the way for the topic of this thesis: the ?rst

search for muon neutrinos from di?use astronomical sources with the AMANDA-II

detector.

3

Chapter 2

High Energy Neutrino Physics and

Astrophysics

2.1 Cosmic Rays

Cosmic rays are perhaps one of the oldest, most puzzling creatures known

to Man. They are known to consist of mostly protons and also heavier atomic

nuclei, yet their origin is not yet fully understood. However, it is clear that nearly

all cosmic rays come from outside the solar system, but from within the galaxy.

The most prevalent theory is that most cosmic rays are accelerated by supernovae

explosions. The case for supernovae explosions is strengthened by the realization

that the ?rst order Fermi acceleration at a strong shock naturally produces a

spectrum of cosmic rays consistent with what is observed.

The energy spectrum of cosmic rays is well described by the power-law

dN

dE

/ E

? ?

(2.1)

where ? is the spectral power index. The value of the spectral index is constant

4

at ? = 2:7 for most energies. However, around 3 PeV, the region known as \the

knee", the slope steepens to a value of ? = 3:0. Observations above 5 EeV, the

region known as \the ankle", indicate a ?atter spectrum. Figure 2.1 shows the

di?erential energy spectrum of cosmic rays.

The same engines that produce the highest energy cosmic rays may also

produce neutrinos. Hence, the search for the origin of the highest energy cosmic

rays and the search for high energy neutrinos are intimately related.

2.1.1 Fermi Acceleration

Fermi acceleration [13, 14] is commonly accepted as the most plausible ex-

planation for the particle acceleration as it can reproduce the observed spectrum

of cosmic rays. The acceleration of particles to non-thermal energies takes place

in supersonic shock waves. These accelerated particles are theorized to be present

in supernovae, jets produced by active galactic nuclei (AGN), and other violent

astronomical objects.

Particles gain energy in Fermi acceleration through the transfer of kinetic

energy from shocked material in repeated \encounters" with the material. First-

order Fermi acceleration describes the interaction of particles with a plane shock

front, while second-order Fermi acceleration describes interactions of particles

with moving clouds of plasma. These scenarios are illustrated in Fig. 2.2 and

Fig 2.3. The main di?erence between the two cases is that in second-order Fermi

acceleration particles can gain or lose energy in a given encounter. However, after

many encounters there is a net gain in second-order Fermi acceleration. The

5

Atmospheric

Neutrinos

Figure 2.1: The cosmic ray spectrum adapted from [12].

6

upstream

downstream

−u

E

E

V = −u + u

2

1

2

1

1

Figure 2.2: First order Fermi acceleration by a plane shock front. Adapted from

[15].

E

E

V

1

2

Figure 2.3: Second order Fermi acceleration by moving, partially ionized gas cloud.

Adapted from [15].

following derivation for ?rst-order Fermi acceleration follows that given in [15].

Consider a relativistic particle with energy E

1

that encounters a plane shock

front at an angle ?

1

as shown in Fig 2.2. In the rest frame of the shock, the particle

has an energy

E

0

1

= ? E

1

(1 ? ?cos?

1

)

(2.2)

where ? and ? ? V=c are the Lorentz factor and velocity of the shock respectively

and the primes denote the quantities measured in the frame moving with the

7

shock. Transforming the energy to the rest frame of the particle gives

E

2

=? E

0

2

(1+?cos?

0

2

):

(2.3)

Since magnetic ?elds in the shock ?eld produce elastic scattering, E

0

2

=E

0

1

. Thus,

the energy change, ?E, for the encounter described by ?

1

and ?

2

is given by

?E

E

1

=

1 ? ?cos?

1

+?cos?

0

2

? ?

2

cos?

1

cos?

0

2

1 ? ?

2

? 1:

(2.4)

Averaging over cos?

1

and cos?

0

2

gives ?E ˘ (4=3)?E

1

= ?E

1

. Thus, a

particle encountering a shock increases its energy in proportion to its original

energy. After n encounters, the particle's energy is given by

E

n

=E

0

(1+?)

n

(2.5)

where E

0

is the energy of the particle before the encounter. The number of

particles to reach an energy E is then given by

n=

log

E

E

0

1+?

:

(2.6)

If the probability of particles escaping the acceleration region is given by

P

esc

, then after n encounters the escape probability is given by

P

n

= (1 ? P

esc

)

n

:

(2.7)

The number of particles accelerated to energies greater than E is then

N(>E) /

1

X

m = n

(1 ? P

esc

)

m

=

(1 ? P

esc

)

n

P

esc

:

(2.8)

8

Substituting n gives

N(>E) /

1

P

esc

?

E

E

0

??

?

(2.9)

where

?=

log

1

1 ? P

esc

log1+?

:

(2.10)

For a di?erential spectrum equation 2.9 takes the form

dN

dE

/

1

?

1

P

esc

?

E

E

0

??

( ? +1)

(2.11)

As shown in [15] for shock fronts the spectral index can be approximated as

? =1+

4

M

2

(2.12)

where M = the Mach number ˛ 1. In this case, the spectral index tends to ? ˘ 1

which corresponds to a di?erential index of (? + 1) ˘ 2 at the source. Neutrinos

that result from Fermi accelerated protons/pions are expected to have this energy

spectrum, E

? 2

, when they reach the earth.

This simpli?ed derivation uses the test particle assumption, meaning the

particles being accelerated did not a?ect the conditions in the acceleration region.

More detailed calculations can result in ? ˇ 2:0 ? 2:4. Taking into account the

known energy-dependent leakage of cosmic rays out of the galaxy modi?es the

spectrum by ?? of 0.3 to 0.6. This leads to a ?nal spectral index for ?rst order

Fermi accelerations is ? ˘ 2:7 for cosmic rays [15].

9

2.2 Neutrinos as a Source of Information

The universe has been explored throughout the electromagnetic spectrum,

from radio waves to high energy gamma rays. However, it has not been until

recently that we have been able to examine the universe with a new particle, the

neutrino.

The advantages of using neutrinos as information carriers is demonstrated

in Fig. 2.4. Foremost, neutrinos are not absorbed at high energies by ambient

matter or photon ?elds like their photon counterparts. Photon absorption happens

at the Mpc scale [1] and is the limiting adversary faced by gamma ray astronomy.

Secondly, unlike cosmic rays, which are de?ected by magnetic ?elds as they travel

through space, neutrinos always point directly back to their source.

Astrophysical sources produce high energy gamma rays primarily by radia-

tive processes from accelerated electrons, such as Compton scattering and syn-

chrotron radiation, as well as the decay of pions:

p+? ? ! p+ˇ

0

u

? ! 2?:

(2.13)

In contrast, neutrinos are produced via hadronic processes. The primary sources

of these neutrinos are through the decay of pions and kaons:

p+X ? ! ˇ

?

+Y

u

? ! ?

?

+?

?

(??

?

)

u

? ! e

?

+ ?

e

(??

e

) + ??

?

(?

?

)

(2.14)

10

Accelerator

Target

Opaque matter

N

S

p

p

p

Detector

Earth

p

ν

ν

μ

μ

γ

ν

Figure 2.4: Neutrinos can travel from greater distances than photons because they

are not absorbed by ambient matter or photon ?elds. Furthermore, neutrinos are

not de?ected by magnetic ?elds and always point directly back to their source,

unlike cosmic rays [16].

11

p+X ? ! K

?

+Y

u

? ! ?

?

+ ?

?

(??

?

)

u

? ! e

?

+ ?

e

(??

e

) + ??

?

(?

?

)

(2.15)

p+X ? ! K

0

L

+Y

u

? ! ˇ

?

+?

?

+?

?

(??

?

)

u

? ! ˇ

?

+e

?

+?

e

(??

e

)

:

(2.16)

Hence, high energy astronomy has the ability to di?erentiate between hadronic

and electronic models of gamma ray emitters such as supernovae remnants, gamma

ray bursts, or active galactic nuclei.

2.3 Expected Sources of Astronomical High Energy

Neutrinos

2.3.1 The Atmosphere

Atmospheric neutrinos are produced in abundance in Earth's upper atmo-

sphere. These neutrinos have energies that span a few MeV up to the highest

energy cosmic rays. They serve as both a background and calibration beam in

the search for extraterrestrial neutrinos.

Cosmic rays constantly bombard Earth's atmosphere, producing extensive

air-showers when they interact with nuclei in the air. At the energies relevant

to the AMANDA detector, cosmic rays consist of protons and helium nuclei with

12

some contributions from heavier nuclei. The spectrum of cosmic rays follows a

power law, E

? 2 : 7

, in the energy range of interest for AMANDA.

Cosmic ray nuclei interact producing new particles, such as pions and kaons.

Neutrinos arise primarily from the decay of these pions and kaons as described by

equations 2.14 - 2.16. These neutrinos are referred to as atmospheric neutrinos

because of their origin. The atmospheric neutrino spectrum follows a power law

of E

? 3 : 7

, which is steeper than that of the cosmic rays they come from as shown

in ?g 2.1. The reason for this is that at high energies, pions tend to interact more

often than they decay.

Another reaction that can create neutrinos in the atmosphere is the decay

of charm particles, primarily D mesons. Charmed particles have a short lifetime.

Consequently, the neutrinos that arise from these decays are referred to as prompt

neutrinos. Prompt neutrinos constitute only a few percent of the neutrino ?ux

at 1 TeV and become a dominant source of neutrinos in the atmosphere only

at higher energies. The precise energy and ?ux of prompt neutrinos is heavily

model-dependent.

Although the angular distribution of cosmic rays is isotropic, the spectrum

of atmospheric neutrinos is dependent on zenith angle. Near the horizon the ?ux

is more prominent. This is because pions, kaons, and muons produced nearly

tangent to Earth have longer ?ight times through the atmosphere. Thus, they

have more of a chance to decay into neutrinos. The e?ect is seen as a symmetric

peak in zenith angle about the horizon in Fig 2.5.

13

Cosine Zenith Angle

10

3

10

4

-1 -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

Figure 2.5: The atmospheric neutrino spectrum has a symmetric peak about the

horizon.

14

2.3.2 The Galactic Disk

Galactic neutrinos are produced through the hadronic interactions that hap-

pen when cosmic rays di?use though the interstellar medium. Most of the energy

lost in these interactions goes into the production of mesons. These mesons sub-

sequently decay into gamma rays and neutrinos. Since there is no atmosphere in

the galactic disk, most of the mesons produced decay into neutrinos. Hence, the

spectrum of gamma rays and neutrinos resembles that of the cosmic ray spectrum

in the interstellar medium,

dN

dE

= E

? 2 : 7

. The ?ux of galactic neutrinos is small

and they have a steep spectrum. Thus, they only become an issue above 1 PeV

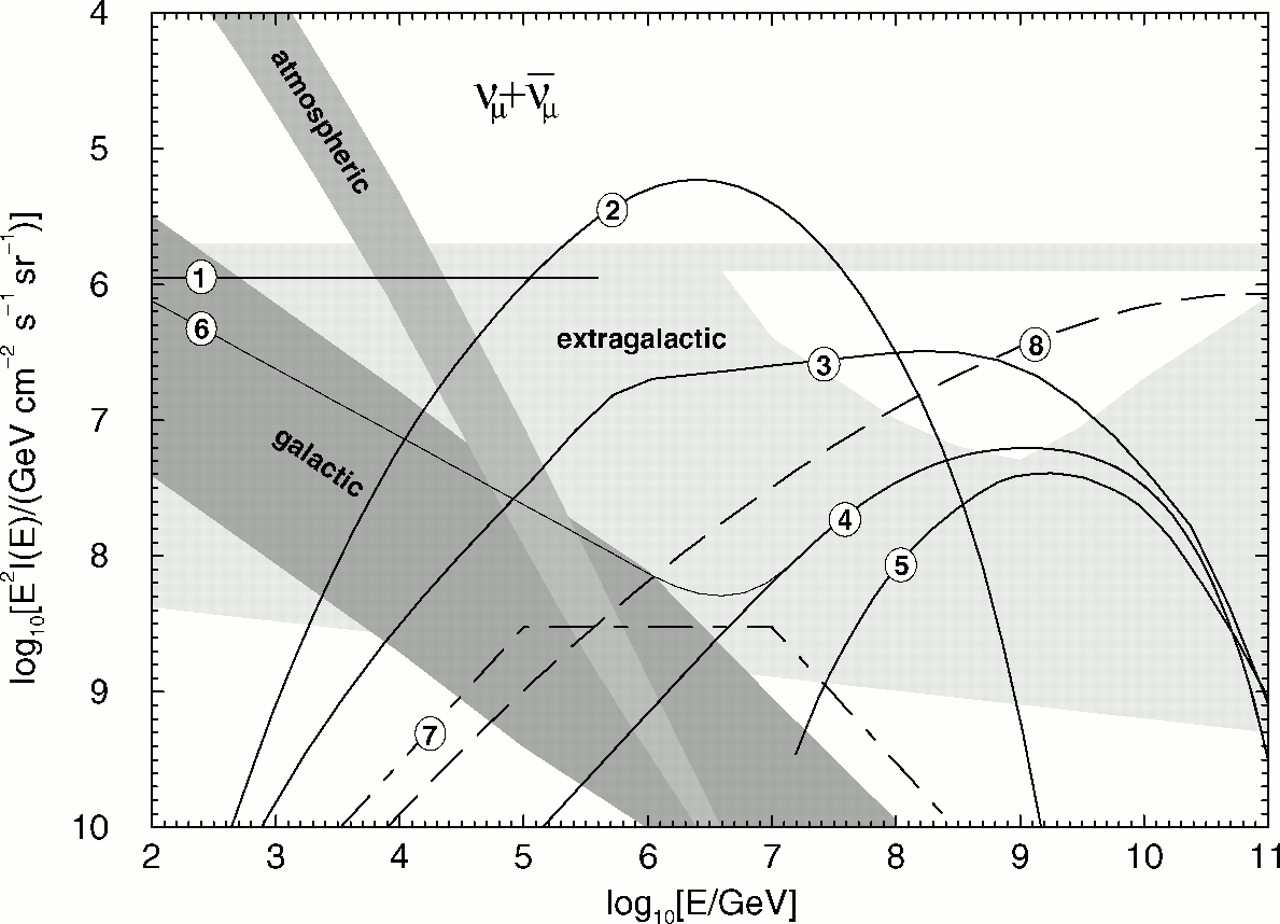

(see Fig. 2.7). Even then, the AMANDA detector's location at the south pole

makes galactic neutrino detection challenging. Thus, they pose no background to

this analysis.

2.3.3 Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN)

One promising source of extragalactic neutrinos is active galactic nuclei

(AGN). AGN are among the most energetic objects in the universe. They emit as

much energy as an entire galaxy, but are extremely compact. Their luminosities

have been observed with ?ares extending over periods of days. The frequency of

the ?aring can vary from hours to years. All wavelengths of radiation from radio

waves to TeV gamma rays are emitted from AGN.

AGN are believed to be powered by accreting super-massive black holes

lurking in the centers of galaxies. There are two generic models for neutrino

production in AGN: core models and jet models. The main di?erence in these

15

models is where the neutrinos are produced.

In core models, the neutrinos are believed to be produced in Fermi shocks

of protons inside the accretion disk. The shocked protons interact with protons

or photons in and around the disk producing neutrinos though pion decay as

demonstrated in equation 2.14.

In AGN jet models some of the in-falling matter from the accretion disk is

believed to be re-emitted and accelerated in highly energetic beamed jets that are

aligned with the axis of rotation of the black hole as shown in Fig 2.6.

The particles in the relativistic jet are assumed to be accelerated by Fermi

shocks in clumps or sheets of matter traveling along the jet with Lorentz factors

of 10-100.

Gamma rays can be produced from electron acceleration by synchrotron

radiation or Compton scattering. In the case of proton acceleration, the thermal

ultraviolet photons or synchrotron photons provide the dominant target for pion

production. These pions subsequently decay to gamma rays and neutrinos via

equation 2.14. Di?erent neutrino spectra are expected from electrons and photons

and are the subject of debate. An observation of high energy neutrinos from these

sources would help resolve the issue of particle acceleration.

2.3.4 Gamma Ray Bursts (GRB)

Gamma Ray Bursts (GRBs) are the most luminous cataclysmic phenomena

in the universe. They can be characterized by their ?ares, which last from a

few milliseconds to a few seconds and have short rise times on the order of a

16

Jet

black

hole

accretion disk

wind

γ-ray

~10

–2

pc

γ

~– 10

Figure 2.6: Possible production mechanism for AGN. Electrons and possibly pro-

tons, which are accelerated in sheets or blobs along the jet, interact with photons

that are radiated by the accretion disk or produced in the magnetic ?eld of the

jet. Taken from [17].

17

millisecond followed by an exponential decay. GRBs are randomly distributed

across the sky.

Although the powering process behind a GRB is still unknown, the short

rise time indicates that they originate from compact objects with diameter of tens

of kilometers. Possible sources of such objects are hyper-novae which result from

the fusion of neutron stars or super-massive star collapse.

The bursts are believed to be produced by the dissipation of the kinetic en-

ergy of a relativistically expanding ?reball. Gamma rays could be produced by the

decay of neutral pions or emission of synchrotron radiation (possibly followed by

inverse Compton scattering) by relativistic electrons accelerated in the dissipation

shocks.

In this model, the ultra-relativistic expansion of electron-positron plasma

forms a shock wave. Protons may also be accelerated by Fermi acceleration in the

same region the electrons are accelerated. Neutrinos would then be created by

photo-meson production of pions in interactions between the ?reball ?-rays and

accelerated protons.

It is interesting to note that the energy released in a GRB is about the same

needed to produce the highest energy cosmic rays, whose origin are still unknown.

2.3.5 Exotic Phenomena

The highest energy cosmic rays observed have energies above 100 EeV and

are di?cult to explain using conventional Fermi acceleration models of charged

particles. Some models [18, 19] suggest that these ultra-high energy cosmic rays

18

are produced by the decay of super-massive \X" particles released from topologi-

cal defects, such as cosmic strings and monopoles, created in cosmological phase

transitions. \X" particles can be particles such as gauge or Higgs bosons or super-

heavy fermions. These particles typically decay into a lepton and a quark. The

quark is then theorized to hadronize into nucleons and pions. The pions can then

decay into photons, electrons, and neutrinos.

2.4 Di?use Source

The most obvious way to search for the neutrino sources described above

is to identify excesses of neutrinos coming from particular sources in the sky.

However, individual sources of high energy neutrinos may not be bright enough to

be resolved by the AMANDA-II telescope. Fortunately, there are a large number of

sources. Thus, the sources produce an isotropic background of neutrinos with high

energies. A large neutrino detector, such as AMANDA-II is sensitive to di?use

?uxes of neutrinos from unresolved sources. A measurement of this background

could be the ?rst evidence of neutrinos from hidden sources.

Searching for neutrinos from di?use sources, which is the topic of this work,

is much more di?cult than looking for a particular point source in the sky as

there is no directional information. However, high energy neutrinos predicted to

come from di?use sources have a much shallower energy spectrum, (E

? 2

), than

the atmospheric neutrino background, (E

? 3 : 7

).

Theoretical bounds can be made on the di?use ?ux of neutrinos from knowl-

19

edge of the di?use ?ux of gamma rays and cosmic rays. In the case of proton

acceleration, gamma rays and neutrinos are produced in parallel. Despite the fact

that neutrinos escape the source with no further interactions while the gamma

rays cascade to lower energies in the source or scatter with the cosmic infrared

background, the integral energy of these particles is the same within a factor of two

[21]. The EGRET experiment[20] aboard the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory

measured the isotropic di?use gamma ray background intensity as

?(E > 30MeV) = (1:37 ? 0:06) ? 10

? 6

E

? 2 : 1 ? 0 : 03

cm

? 2

s

? 1

sr

? 1

GeV: (2.17)

Taking into account the factor of two mentioned above, the upper theoretical

bound of the neutrino ?ux is on the order of 10

? 6

cm

? 2

s

? 1

sr

? 1

GeV. This limit

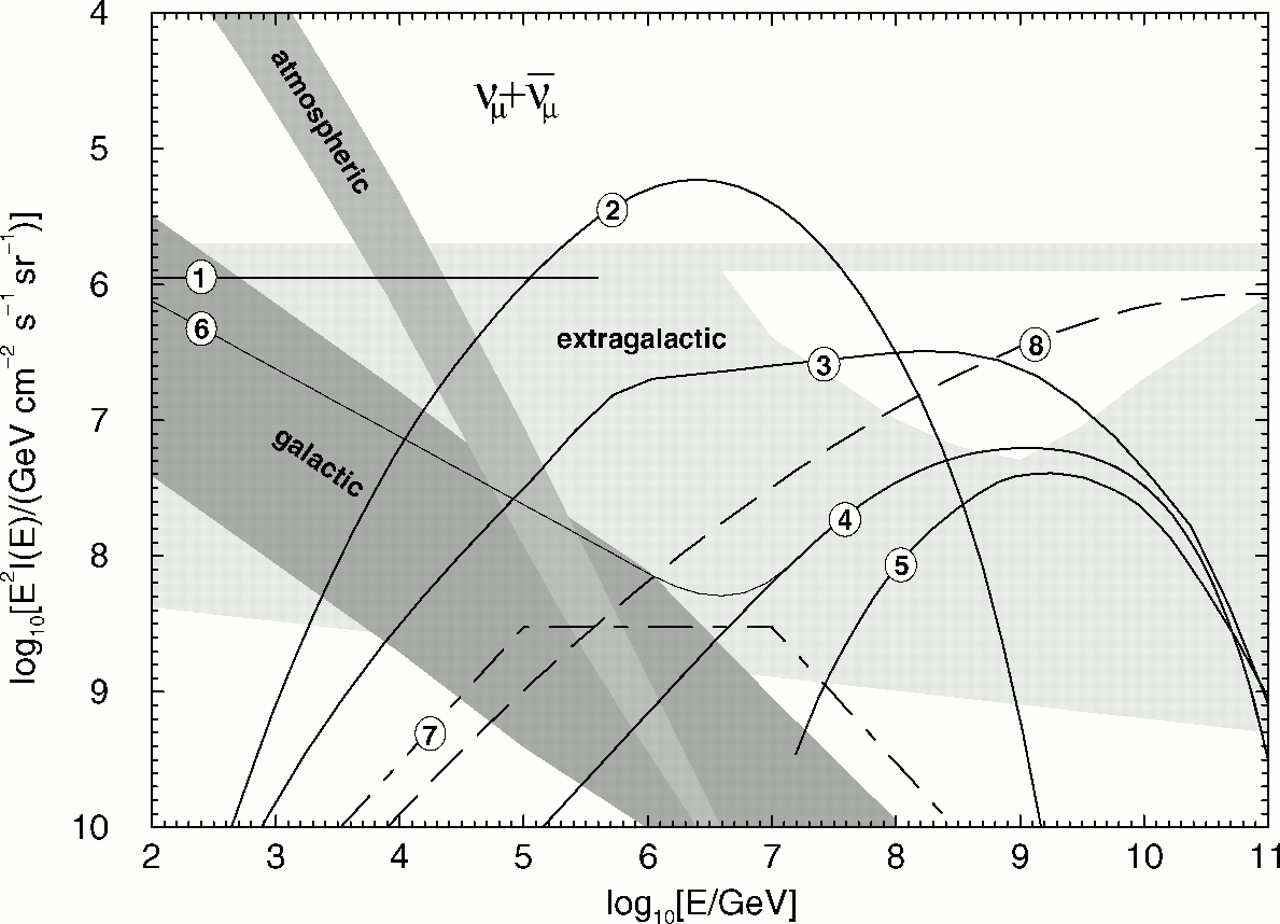

can be seen in ?gure 2.7 as the straight upper boundary of the extragalactic region.

A similar argument can be made for sources where both gamma-ray and

cosmic-ray nucleons escape. For an optically thick source, both protons and neu-

trons are trapped in the source and the gamma ray limit applies. However, for

optically thin sources, it is possible for the neutrons to escape the source without

energy loss and inversely ?-decay into cosmic protons outside the source. These

neutrons then travel una?ected by magnetic ?elds in the Universe. The neutrino

upper bound for these sources is represented by the curved upper boundary of the

extragalactic region in ?gure 2.7.

20

Figure 2.7: Expected ?uxes of ? + ?? intensities for emission from various di?use

sources taken from [21]. Fluxes 1-2 are predicted using the core model of emission

from AGNs [22, 23], while ?uxes 3-6 use the AGN jet (blazar) model [24, 25, 26,

27]. Flux 7 is a prediction of neutrinos from GRBs [28], while ?ux 8 is a neutrino

prediction from topological defects [18, 19].

21

2.5 Neutrino Oscillations

Evidence from GeV scale atmospheric and MeV solar neutrino experiments,

Super-Kamiokande [29] and Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO) [30] strongly

suggest that neutrinos oscillate from one ?avor to another. The LSND accelerator

experiment has also reported observing large neutrino oscillations [31]. This result

is controversial and experiments are under way to con?rm or refute it. In order

to accommodate all three experiments a fourth neutrino, the sterile neutrino (?

s

),

which does not interact has been postulated. The following discussion will consider

the simpli?ed case of two-?avor oscillations.

In order for neutrinos to oscillate from one ?avor to another, neutrinos must

be massive, and the eigenstates for weak interactions must be di?erent than those

for free neutrinos. The probability of a neutrino of ?avor ` and energy E

`

that

travels a distance L in vacuum to oscillate to a neutrino of ?avor `

0

is given by

P

?

`

?

`

0

= sin

2

2?sin

2

ˇ

L

L

osc

(2.18)

where sin

2

2? is the mixing angle between the two neutrinos and L

osc

= 4ˇE

`

=?m

2

is the oscillation length in vacuum.

At their source, neutrinos are produced in the ratio ?

e

: ?

?

: ?

˝

˘ 1 : 2 : 0.

Due to oscillations as they travel through space, the ratio observed at Earth is

1 : 1 : 1 [32]. Thus, muon neutrino ?uxes predicted at their source would on Earth

be observed as one-half the predicted ?ux at the source. This should be kept in

mind when interpreting analysis results as many di?use spectrum ?ux theories do

not take this into account.

22

Chapter 3

Detection of Neutrinos

3.1 Neutrino-Nucleon Interactions

It is well known that neutrinos can not be directly detected. However, a

neutrino or anti-neutrino traveling through matter has some small probability of

interacting through charged-current scattering

?

l

+N ! l

?

+X

(3.1)

??

l

+N ! l

+

+X

(3.2)

where l is the lepton ?avor, N is the target nucleon, and X is a combination of

?nal state hadrons. At high energies, the lepton carries approximately half the

energy of the neutrino. From the kinematics of this reaction, the neutrino and

the lepton will be collinear to a mean deviation of

p

h ?

??

2

iˇ

q

m

p

=E?

(3.3)

which is about 1.75 degrees for a 1 TeV neutrino. The other half of the energy is

released in the hadronic cascade, X, producing a bright, relativity localized ?ash

23

of light.

The cross section for the charged-current neutrino-nucleon interaction in the

rest frame of the nucleon (assuming a relativistic outgoing lepton) is [33]

d

2

˙

dxdy

=

2G

2

F

M

N

E

?

ˇ

?

M

2

W

Q

2

+ M

2

W

?

[xq(x; Q

2

) + xq?(x; Q

2

)(1 ? y

2

)];

(3.4)

where ? Q

2

is the invariant momentum transfer from the neutrino to the outgoing

muon, q and q? are the parton distribution functions of the nucleon, G

F

is the Fermi

constant for weak interactions and M

N

and M

W

are the masses of the nucleon

and W boson. The Bjorken scaling variables, x and y, are given by

x=

Q

2

2M

N

(E

?

l

? E

l

)

(3.5)

and

y =1 ?

E

l

E

?

l

;

(3.6)

where x is the fraction of the nucleon's four-momentum carried by the interacting

quark and y is the fraction of the neutrino's energy deposited in the interaction. At

low energies, the neutrino cross section is four times greater than that of the anti-

neutrino and the cross section is dominated by interactions with valence quarks.

However, at high energies their cross sections become equal as they predominantly

interact with sea quarks in the nucleon, shown in Fig 3.1.

At low energies, ? Q

2

˝ M

W

, and the term in parentheses in equation 3.4

can be neglected. In this region, the neutrino-nucleon cross section rises linearly

with the neutrino energy. However, when Q

2

becomes comparable to M

W

, the

cross section grows more slowly, as seen in Figs. 3.3 and 3.2. This transition occurs

24

Figure 3.1: Charged-current neutrino cross sections as a function of energy [33].

The solid line is based on the CTEQ3 parton distributions. The dashed and

dotted lines are from older measurements.

25

Figure 3.2: Di?erential cross section for neutrino-nucleon scattering for neutrino

energies between 10

4

GeV and 10

12

GeV from [33].

at approximately 3.6 TeV. In this same region the average value of y begins to

fall which leads to an increase in the momentum transfer to the muon and, hence,

a longer muon range. The longer muon range helps o?set the slower growth in

neutrino cross section.

3.2 Lepton Signatures

After a neutrino interacts with a nucleon it produces one of three di?erent

leptons. Each of these leptons leaves a distinct signature in neutrino detectors.

Below the critical energy of about 600 GeV, secondary muons from muon neutrinos

deposit their energy continuously at a rate of ˘ 0:2 GeV per meter as they travel in

a nearly straight line through the detector. The resulting experimental signature

is a long linear deposition of light due to Cherenkov radiation, described in section

26

Figure 3.3: Energy dependence of the average in-elasticity of neutrino-nucleon

interactions from [33].

3.3.1, that leaves a track with length of hundreds of meters, kilometers, or even

tens of kilometers, depending on the initial energy of the muon. A typical muon

signature in the AMANDA detector is shown in Fig. 3.4.

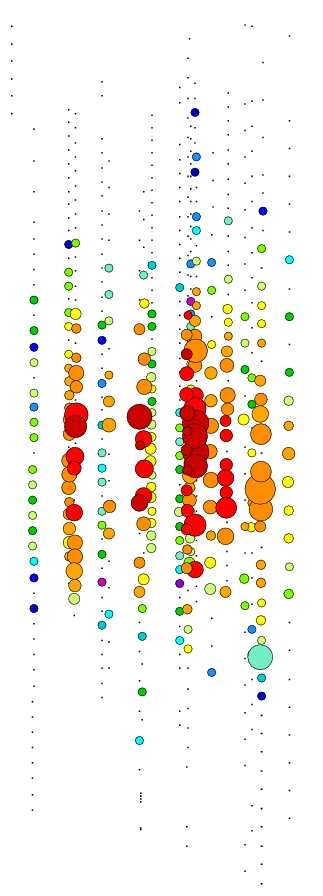

The signature for an event produced by interactions from an electron neu-

trino is a bright, spherical deposition of Cherenkov light generated by an elec-

tromagnetic cascade, and is shown in Fig. 3.5. Unlike muons, which have a

long range, electrons quickly dissipate their energy by radiative processes such

as bremsstrahlung and pair production. The electromagnetic cascade reaches its

maximum after a few meters, a small distance compared to the spacing of the op-

tical modules. Thus, an electron-neutrino event in the AMANDA detector looks

like a point source of light.

The most striking lepton signature, not seen in AMANDA due to the detec-

tor's small size, is that of the tau neutrino. When a tau neutrino interacts with a

nucleon, it produces a tau particle and a hadronic cascade at its interaction point.

Subsequently, the tau particle will travel some distance and decay. This decay

27

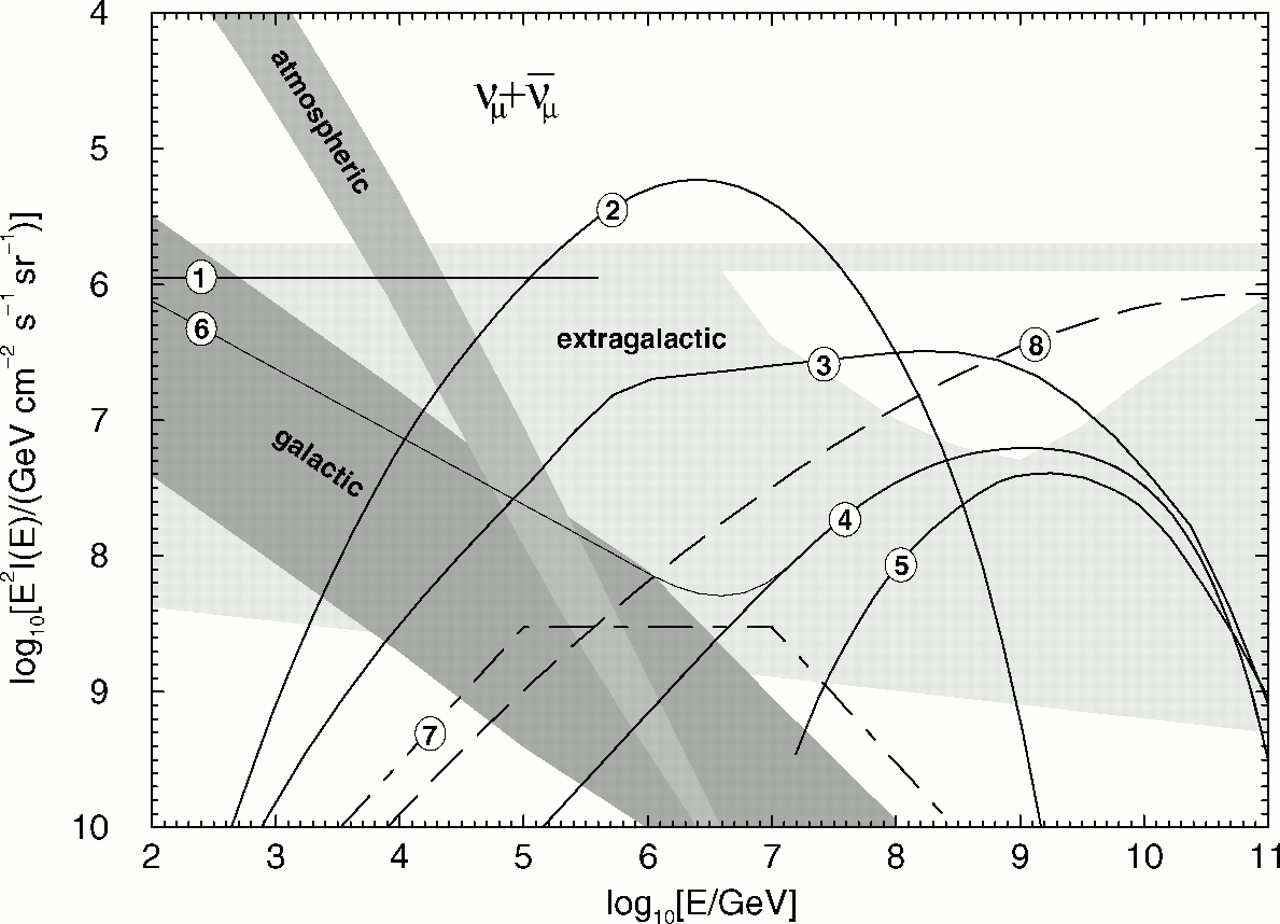

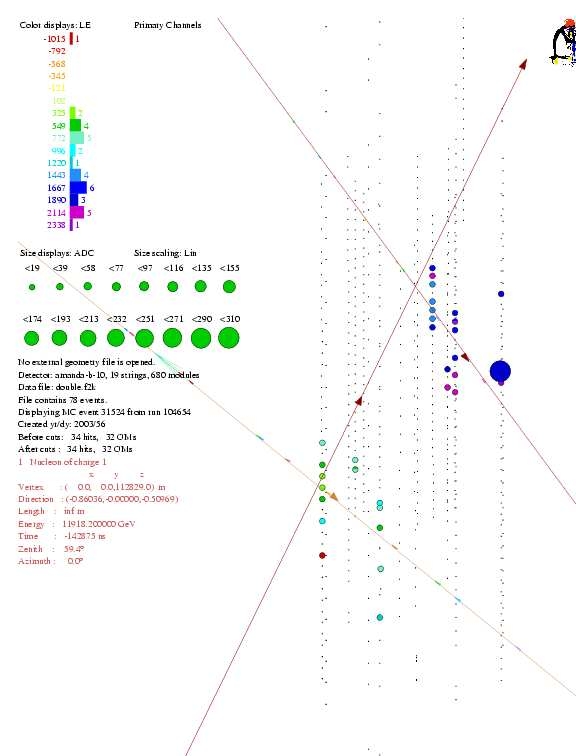

Figure 3.4: A muon event in the AMANDA detector. As the muon passes through

the detector, light is emitted at a constant rate.

28

29

will produce a second hadronic cascade. This cascade is very di?cult to resolve

from the ?rst, making it indistinguishable from a cascade produced by an electron,

except at very high energies where the tau may travel hundreds of meters. For

events that are contained within the detector, this \double bang" topology is a

very distinctive signature, as seen in Fig. 3.6.

3.3 Muon Energy Loss

3.3.1 Cherenkov Radiation

A charged particle moving through a transparent medium with refractive

index n > 1 with speed v > c=n will produce Cherenkov radiation. Cherenkov

radiation is emitted at an angle of

cos?

C

=

1

?n

:

(3.7)

For energies relevant to AMANDA, ? ˘ 1. The refractive index of ice is n = 1:34.

Substituting these values into equation 3.7 yields

?

c

=41

?

:

(3.8)

The energy loss due to Cherenkov radiation is ˘ 10

3

MeV=cm, relatively

small compared to the total ionization loss of approximately 2 MeV=cm for mini-

mally ionizing particles [35]. Nonetheless, a muon emits ˘ 200 photons/cm, which

is enough for detection [36].

30

Figure 3.6: A tau event in the future IceCube detector. The two cascades of light

are produced by the initial neutrino-nucleon interaction and subsequent decay of

the tau particle.

31

3.3.2 Stochastic Energy Deposition

Muons can lose energy through several mechanisms: ionization, bremsstrahlung,

pair production, and photo-nuclear processes. Ionization is a quasi-continuous

process and can be treated continuously, while the others are stochastic in nature.

The average rate of stochastic energy loss is nearly proportional to the muon en-

ergy. The total rate of energy loss of a muon traveling through ice per unit length

can be parameterized by

?

dE

?

dx

= a(E

?

)+b(E?) ? E

?

(3.9)

where a is the energy loss due to ionization and b ? E is the energy loss due to

stochastic processes [34].

In ice the value of a is approximately 0:2GeV=m [34] and value of b is

approximately 3:4 ? 10

? 4

m

? 1

. Thus, stochastic events are the main component

of energy loss for muons above 600 GeV.

32

Chapter 4

The AMANDA Detector

AMANDA (the Antarctic Muon and Neutrino Detector Array) is an ice Cherenkov

telescope located beneath the ice at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. The

detector is an array of 677 photomultiplier tubes and was built over the course

of ?ve years. Its primary mission is the detection of neutrinos originating from

astrophysical sources.

4.1 History

The ?rst e?ort to build an under-ice neutrino detector was in the austral

summer of 1993/94. Four strings, each with 20 optical modules, were deployed at

depths between 800 and 1000 meters. This detector became known as AMANDA-

A. Studies of the ice properties at these depths showed the absorption length to be

around 200 meters at the peak absorption of the photomultiplier tubes (PMTs)

of 400 nm. At the same time, the scattering length was on the order of 10-20 cm,

a value too small to allow the reconstruction of muon trajectories. The scattering

length was dominated by tiny air bubbles trapped in the ice. It was thought

33

that these bubbles would be absent at 800 m as a result of the phase transition

that occurs as the increasing pressure transform the air bubbles into air hydrate

crystal. However, due to the low temperatures at the south pole, the di?usion

of air molecules into the ice crystalline structure slows down. Thus, the bubbles

only completely disappear at about 1300 m [37].

Learning from the experiences with the AMANDA-A array, the 19 strings of

AMANDA-II were deployed at greater depths (1500m - 2000 m) in stages during

the austral summers from 1995-2000.

4.2 The Detector

The AMANDA detector consists of a three-dimensional array of optical mod-

ules (OMs). Each OM consists of an 8" Hamamatsu PMT housed in a glass pres-

sure sphere. The OMs are connected to the surface by an electrical cable which

serves two purposes. The cable provides the high voltage necessary to operate the

PMT and transmits signals from the PMTs back to the data acquisition (DAQ)

system electronics at the surface.

As the AMANDA detector grew through years of deployment, the hardware

used to construct the detector matured. The ?rst 4 strings of what is now known

as the AMANDA detector (then called AMANDA-B4) were deployed in the aus-

tral summer of 1995-96. These 86 OMs where connected to the surface by coaxial

cable, which provided protection against electronic crosstalk in the cables. Unfor-

tunately, coaxial cable has limitations. Coaxial cable is quite dispersive, resulting

34

in distortion during the course of transmission to the surface (10 ns PMT pulses

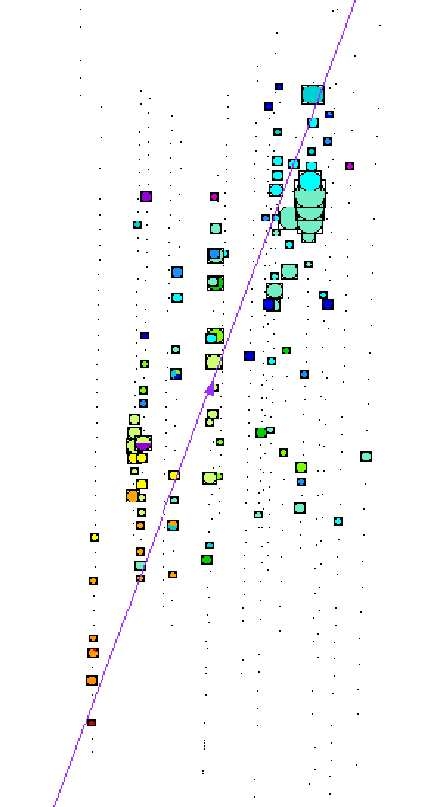

arrive at the surface with a width of more than 400 ns). Coaxial cable is also

quite thick, limiting the number of cables that could be bundled together.

For these reasons the next 6 strings, which were deployed during the austral

summer of 1996-97, used twisted pair cables. These 6 strings brought the total

number of OMs in the array to 302. This new array was named AMANDA-B10.

The twisted pair cables had less dispersion (150 ns - 200 ns) and allowed more

cables per string. However, a great deal of electronic crosstalk was observed in

these strings.

During the austral summer of 1997-98 another 3 strings were deployed bring-

ing the total number of OMs to 428. These strings had both optical ?bers and

traditional twisted pair cables. The optical ?bers were essentially dispersion free

and crosstalk free. However, they were quite fragile and nearly 10% were dam-

aged during the refreeze process. Another change in the deployment of these three

strings was that they were to lie at a depth between 1200 m - 2400 m in order to

study the optical properties above and below the detector.

The last strings to be added to the array were strings 14-19 in the aus-

tral 1999-2000 summer. This marked the completion of the AMANDA-II detec-

tor. All OMs on these strings were connected to the surface via optical ?bers

and traditional twisted pair cables. Some of the modules deployed during this

year contained experimental digital technologies under investigation for future ice-

Cherenkov detectors. String 18 is comprised entirely of digital optical modules

35

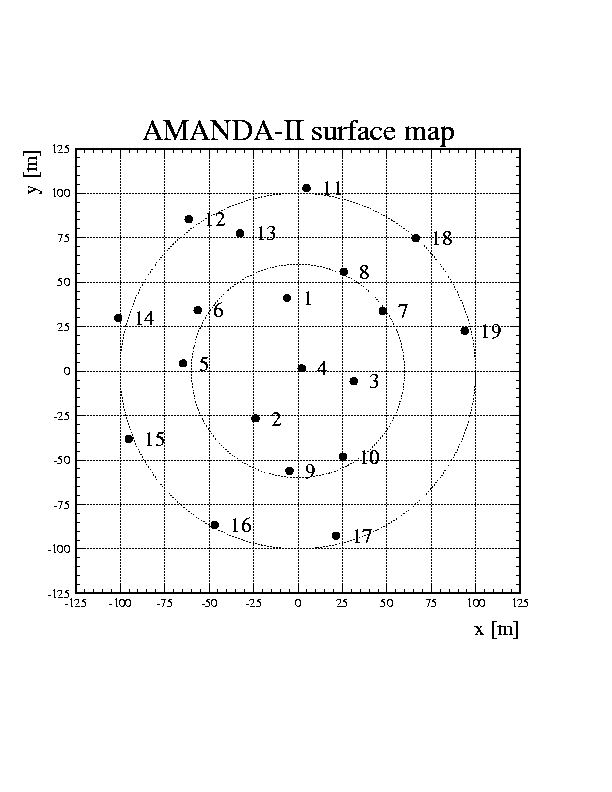

Figure 4.1: Top view of the AMANDA-II detector. The radius of the detector is

approximately 100 meters.

(DOMs). These modules contained analog transient waveform digitizers (ATWDs)

which record and digitize the signal in situ and then transmit them to the surface.

This technology results in the full retention of waveform information without the

need for optical ?bers. However, the DAQ electronics are buried with the OMs in

the ice, hence, beyond the possibility of repair or upgrade.

The complete AMANDA-II detector contains 19 strings, 677 OMs and in-

struments 0.015 km

3

of ice. It has a diameter of 200 m and a height of 500 m. The

modules on each string are separated by 10 m - 20 m, depending on the string.

The strings are arranged in three concentric circles and separated by 30 m - 60

m. Figures 4.1 and 4.2 show the layout of the AMANDA detector.

36

120 m

snow layer

?✁?

?✁?✂

✂

optical module (OM)

housing

pressure

Optical

Module

silicon gel

HV divider

light diffuser ball

60 m

AMANDA as of 2000

zoomed in on one

(true scaling)

200 m

Eiffel Tower as comparison

Depth

surface

50 m

1000 m

2350 m

2000 m

1500 m

810 m

1150 m

AMANDA-A (top)

zoomed in on

AMANDA-B10 (bottom)

AMANDA-A

AMANDA-B10

main cable

PMT

Figure 4.2: Schematic of the geometry of AMANDA-II. AMANDA-A and

AMANDA-B10 are shown in expanded view in the center. An optical module

is blown up on the right. The Ei?el Tower is shown to illustrate the scale.

37

The ?rst strings of the IceCube detector are scheduled to be deployed in

the austral summer of 2004-05. The entire IceCube array will contain some 4800

OMs, 80 strings and instrument 1 km

3

of ice. It is scheduled to be completed

in 2009-10. All of the OMs in the IceCube array will use the DOM technology.

IceCube will be deployed between the depths of 1400 m and 2400 m.

4.3 Data Acquisition

The AMANDA detector trigger can come from a variety of sources. In

normal mode, the detector is triggered by the detection of photons by a set number

of OMs in a preset window of time (majority trigger). For the AMANDA-II year

2000 data set, 24 OMs were required to receive at least 1 photo-electron in a

2:1 ?sec time period. The trigger rate was approximately 100 Hz.

The data acquisition (DAQ) system, located on the surface, is responsible

for reading out event information and storing it to disk. Information read and

stored by the DAQ includes the leading edge time (LE) and the width or time-

over-threshold (TOT) in the time window ˘ 22?sec before and ˘ 10?sec after

the trigger time. The DAQ also records the amplitude of pulses arriving from the

OMs. The analog digital converter (ADC) information is recorded during a time

window of ? 2?sec around the trigger time. The event time is obtained from a

Global Positioning System (GPS) unit.

A majority trigger in AMANDA is formed based on hit multiplicity. When

an OM detects a photo-electron it sends a pulse to the surface where it is received

38

by a Swedish Ampli?er (SWAMP) which ampli?es the signal. A copy of the signal

is then sent to discriminators where the signal is converted to a 2 ?sec square pulse.

The discriminator sends its output to the Digital Multiplicity Adders (DMAD)

where multiple signals are summed and compared to a preset threshold. In 2000,

this threshold was set at 24 channels. When the sum crosses the threshold, a stop

signal is sent to all time digital converters (TDCs) and a veto of several ?sec is

sent to the trigger. All channels are then read out and the system reset.

4.4 Ice Properties

Understanding the properties of the ice is crucial for the operation of the

AMANDA-II detector. Thus, the scattering and absorption properties, which

a?ect the timing and number of photons that reach the OMs, must be throughly

understood. Numerous studies using both in-situ light sources and atmospheric

muons have been conducted to determine the ice properties.

The ice is characterized using three parameters: the scattering length ?

b

(or

the scattering coe?cient b = 1=?

b

), the absorption length ?

a

(or the absorption

coe?cient a = 1=?

a

), and the average of the cosine of the scattering angle (˝

s

=

h cos? i . The e?ective scattering length is then de?ned as ?

eff

b

= ?

s

=(1 ? ˝

s

) and

its coe?cient is b

e

= 1=?

eff

b

. The e?ective scattering and absorption coe?cients

are shown in Figs. 4.3 and 4.4 as a function of wavelength.

Dust grains (about 0.04 microns in size) are the biggest contributors to

scattering and absorption in the antarctic ice below 1400 meters. Air bubbles,

39

1200

1400

1600

1800

2000

2200

2400

0.01

1/100

0.02

1/50

0.03

1/33

0.04

1/25

0.05

1/20

0.06

1/16

0.07

1/14

0.08

1/12

0.09

1/11

0.007

1/143

0.008

1/125

0.009

1/111

absorption coefficient

[

m

-1

]

depth

[m]

λ

= 532 nm

λ

= 470 nm

λ

= 337 nm

λ

= 370 nm

Figure 4.3: Absorption coe?cients as a function of depth at various wavelengths

[38].

which were the largest scatterers in the AMANDA-A detector, are squeezed into

air hydrate crystals which have nearly the same index of refraction as ice at

AMANDA-II depths and pose no problems to light detection.

Although the glacial ice in which AMANDA-II is embedded is nearly uni-

form, climatological events in Earth's past, such as ice ages, have left layers of

impurities in the form of dust, soot, etc. These dust layers a?ect the optical

properties of the ice and a?ect photon propagation.

The ?rst measurements of the scattering and absorption coe?cients of these

layers was done using a YAG laser at a frequency of 532 nm. Figure 4.5 shows

the e?ective scattering coe?cient as a function of depth in the detector. The dust

40

800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000 2200 2400

1

0.1

0.02

1/1

1/10

1/50

scattering coefficient

[

m

-1

]

depth

[m]

A

BC

D

bubbles

dominate

λ

= 532 nm

λ

= 470 nm

λ

= 337 nm

λ

= 370 nm

Figure 4.4: Scattering coe?cients as a function of depth at various wavelengths

[38].

layers are visible as peaks in the scattering coe?cient while the clear layers are

visible as valleys.

41

Figure 4.5: Scattering coe?cient as a function of depth, indicating the presence

of dust layers. On the left side of the plot the depth of the OMs in relation to the

dust layers are shown [39].

42

Chapter 5

Event Reconstruction and Analysis

Tools

Reconstruction algorithms in AMANDA, like the hardware used to build it, have

developed over time. Reconstructions for both muon tracks and cascades are based

on the principle of maximization of a likelihood function. Due to how sparsely

the AMANDA detector is instrumented, only a limited set of parameters can

be constrained for each event. For muons, these parameters are direction (?; ˚),

position(x; y; z), and time (t).

5.1 Direct Walk Reconstruction

The direct walk [40, 41, 42] method of reconstruction is a ?rst guess method

of reconstruction based on pattern recognition of selected hits from photons that

have not scattered much in the ice. First guess methods of reconstruction are very

fast analytic algorithms that are used as initial track guesses for more complicated

algorithms which will be described in the following sections.

43

The direct walk algorithm looks for track elements which are pairs of hits

consistent with a close track such that

?

?

?

?

j r~

1

? r~

2

j

c

? j t

1

? t

2

j

?

?

?

?

<30ns

(5.1)

where r~

i

is the position of the ith hit and t

i

is the time of the ith hit. Associated

hits, those with small time residuals and appropriate distance from the track

element based on time residuals, are selected. Quality criteria such as the number

of associated hits, the spread of associated hits, and the hit density along the

track element are applied. Track elements that pass these criteria are called track

candidates. The ?nal ?rst guess track is then found by searching for clusters in

zenith angle of track candidates and calculating the mean of all track candidates

belonging to the cluster.

5.2 Maximum Likelihood Reconstruction

The maximum likelihood method [42] is a generalization of the ˜

2

method.

In the limit of Gaussian uncertainties the likelihood, L , is related to ˜

2

by

? 2ln L = ˜

2

. These methods attempt to ?nd the track hypothesis that max-

imizes the likelihood by minimizing ? log L with respect to the track parameters.

In general, the likelihood for a given event E

0

, which is a collection of detector

responses R

i

and a hypothesis H

j

, is written as

L (E

0

j H

j

) =

Y

i

L

i

( R

i

j H

j

):

(5.2)

If the hypothesis is true, it then generates the observed pattern of hits. The

hypothesis is then allowed to vary and an optimization routine is used to ?nd

44

the location H

0

of the global extremum of L . The responses f R

i

g recorded by

AMANDA are the time, t

i

, and duration, TOT

i

, of each PMT signal and the peak

amplitude, A

i

, of the largest pulse in each PMT.

In the case of muon reconstruction, one assumes that the Cherenkov radi-

ation is generated by a single in?nitely long muon track. This is a reasonable

assumption for the energies of this analysis which simpli?es and speeds up the

calculation and optimization. For muons, this reduces the function H to six-

dimensions H = H (~x; ?; ˚; t).

5.2.1 Time Likelihood

By applying the assumption of an in?nitely long muon track we arrive at

the simpli?ed likelihood function. The function depends on the arrival time of the

light,

L =

nhits

Y

i =1

p

?

t

i

res

j d

i

; ?

i

:::

?

;

(5.3)

where t

i

res

is the time delay, d

i

is the distance of the OM from the track, and

?

i

is the orientation of the OM relative to the track. The probability density

function of single photons, p (t

i

res

j d

i

; ?), was generated by parameterizing Monte

Carlo simulations of photon propagation in ice [43].

The negative logarithm of the likelihood function, ? log L , is then minimized

using a Simplex [44] algorithm in an iterative technique, which performs multiple

reconstructions of the same event. Each reconstruction starts with a di?erent

initial track hypothesis. The results of all iterations are compared to each other.

45

The lowest value of ? log L is taken as the reconstructed track.

5.2.2 Bayesian Likelihood

Bayes' theorem allows us to fold in information independent of the measure-

ment into the likelihood function. The theorem states

P (A j B)P (B) = P (B j A)P (A):

(5.4)

Identifying A with the hypothesis H and B with the hit pattern E and solving

for P(H j E) gives

P (H j E) =

P (E j H)P (H)

P (E)

:

(5.5)

The quantity P (E j H) is the likelihood that the given set of hits would be gener-

ated by the hypothesis of interest. P (E) is the probability that a given pattern of

hits is observed. This quantity is independent of track parameters and is therefore

constant. P (H) is known as the prior and does not depend in any way on the

measurement. It is the probability of observing the track and can be calculated

prior to the measurement. Thus, P (H j E) is the probability of the hypothesis

after E is taken into account.

Bayesian event reconstruction [45] uses the prior probability function shown

in Fig. 5.1. This function is ?at over the up-going hemisphere and dependent on

zenith angle in the down-going hemisphere. Reconstructing using this technique

requires one to maximize the product of the probability density function and the

prior. Similar to the time likelihood reconstruction, this is done using the Simplex

minimizer and an interactive minimizing technique.

46

Trigger-Level Prior Function

Cos(Zenith)

1

10

10

2

10

3

10

4

10

5

10

6

-1 -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

1

Figure 5.1: The prior function used is ?at over the up-going hemisphere and de-

pendent on zenith angle in the down-going hemisphere [36].

47

Near the horizon the e?ect of the Bayesian reconstruction is strongest. Since

AMANDA-II is narrow, events coming in near the horizon have shorter track

lengths, making it di?cult to constrain the ?t tightly. The prior indicates that

tracks from atmospheric muons are more likely than neutrinos. Thus, the recon-

struction properly chooses the down-going ?t as being more likely.

5.3 Quality Parameters

Quality parameters are used for selection criteria during di?erent stages of

the analysis. Below are descriptions of the parameters that will be used for this

analysis.

5.3.1 Likelihood Ratio

As discussed in the previous section, a Bayesian maximum likelihood ?t is

performed on the sample to ?t muon tracks to the observed events. The functional

form used is the negative logarithm of the likelihood. This analysis uses two

likelihood ratios, up-to-down and track-to-cascade. The likelihood ratio for up-

to-down going events is de?ned as

R

u=d

L

= log(

L

up

L

down

)

(5.6)

and the likelihood ratio for track-like to shower-like events is de?ned as

R

t=s

L

= log(

L

track

L

shower

):

(5.7)

L

up

is the likelihood of the track being up-going and hence from a neutrino and

L

down

is the likelihood of the track being down-going and hence from a cosmic

48

ray. L

track

is the likelihood of the event being from a muon and L

shower

is the

likelihood of the event being from a cascade.

The up/down likelihood ratio is the most powerful parameter for separating

cosmic ray background events (down-going) from signal neutrinos (up-going).

5.3.2 Smoothness

\Smoothness" (S

phit

) is a topological parameter that is de?ned by the dis-

tribution of hits along the track. It measures how consistent the observed pattern

of hits is with the hypothesis of constant light emission by a muon.

5.3.3 Number of Direct Hits

A \direct hit" occurs when a photon is delayed little by scattering in the

ice between production and detection. This delay is measured relative to the

predicted arrival time of an unscattered Cherenkov photon emitted from the ap-

propriate point along the track. Di?erent delay windows exist for counting direct

hits. For this analysis a hit is considered direct when it arrives in a window of

[-15:75] nanoseconds. Thus, N

[ ? 15:75]

dir

, is de?ned as the number of direct hits in an

event.

5.3.4 Track Length

The track length is determined by projecting each of the direct hits onto the

reconstructed track and measuring the distance between the ?rst and last hits.

In this analysis, two di?erent track lengths were de?ned. The ?rst uses a stricter

direct hit de?nition than described above. For this track length, the direct hits

49

are required to arrive in the time window [-15:25] nanoseconds

L

[15:25]

dir

(5.8)

and the second uses the de?nition of direct hits from above

L

[15:75]

dir

(5.9)

where direct hits were required to arrive in the [-15:75] nanosecond window.

5.3.5 Zenith Angle

In this analysis, the zenith angle of the best up-going ?t and the zenith angle

of the best down-going ?t are also used in conjunction with the number of direct

hits of the best up-going ?t and the number of hits of the best down-going ?t to

remove coincident muon events from cosmic rays.

5.3.6 Center of Gravity

The center of gravity (

?

cog

!

) of an event is de?ned as the mean position of all

OMs hit by one or more photons in an event. It is represented mathematically as

?

cog

!

=

1

nch

X

nch

i =0

r~

i

(5.10)

where nch is the number of OMs to receive at least one photon and r~

i

is the

distance from the center of the detector to the center of the event.

5.4 The Model Rejection Potential

An upper limit on an expected ?ux can be derived from observation when

an experiment fails to detect an expected ?ux. The method used in this thesis is

50

the model rejection potential [47]. It uses the method developed by Feldman and

Cousins [46] to ?nd the limit. In the Feldman and Cousins method, the upper

limit, ?, is a function of the number of observed events, n

o

, and the number of

predicted background events, n

b

,

? ? ?(n

o

;n

b

):

(5.11)